HEADLINES » HEALTH/SPORT

The Duke Lacrosse Scandal: How the first draft of history is often very wrong

July 18, 2014 · 1 Comments

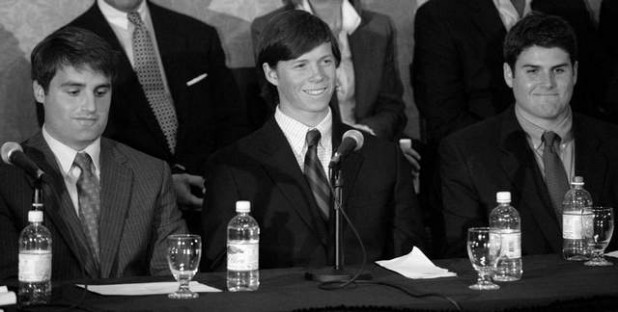

Above: Members of the Duke lacrosse team at a news conference in April 2007, when charges against them were dropped.

By Robert Chambers:

Robert Chambers is the retired president of McDaniel College (formerly Western Maryland College). He is a graduate of Duke University and has also served as a dean at Bucknell and Yale universities. He lives in Gainesville, Florida, and his email address is: [email protected]

DURHAM, N.C., March 28 — Duke University suspended the season of its nationally ranked men's lacrosse team Tuesday while the authorities investigated allegations that a woman from a nearby college who had agreed to dance at a private party attended by many team members had been sexually assaulted.

The incident on March 13, which occurred at an off-campus house owned by the university, has brought into sharp relief long-simmering tensions between the private university and the city. The woman is black, most of the team members are white and law-enforcement officials say they are investigating allegations that racial epithets were shouted at the woman.

Residents, students and faculty members have staged at least five protests in the last four days, including one Tuesday night outside the building where Duke's president, Richard H. Brodhead, was holding a news conference. They are upset with the silence of team members and the university's handling of the case.

—First published account of the Duke lacrosse scandal in the New York Times on March 29, 2006 under the title: “Rape Allegation Against Athletes Is Roiling Duke” by Viv Bernstein and Joe Drape

* * *

THE PRICE OF SILENCE: THE DUKE LACROSSE SCANDAL, THE POWER OF THE ELITE, AND THE CORRUPTION OF OUR GREAT UNIVERSITIES (2014) by William D. Cohan.

This huge volume (almost 700 packed pages) is an often tedious, yet nevertheless riveting account of the biggest scandal in the history of American collegiate sports. For fourteen months, beginning in early 2006, the so-called ”Duke Lacrosse Rape Case” commanded the attention of the entire nation. It seemed to have everything: sex, race, spoiled preppy jocks, over-the-top faculty, sheep-like administrators, clueless trustees, a ravenous press, corrupt law enforcement authorities, unscrupulous lawyers and judges, North vs. South, white vs. black, wealth vs. poverty, and, very much in the mix, a university that millions of Americans loved to hate.

Part of Duke’s problem in the twenty-first century is that its ambitions have far outgrown any semblance of the sleepy Southern school that even long ago already seemed to some to embody all that many people despised about that benighted region of the country. As THE PRICE OF SILENCE strives to show, the University has now completely lost its way.

Lacrosse is a sport long adored in parts of the American Northeast, which is also home to most of our leading male prep schools, among them Delbarton School, the Catholic jewel of wealthy Morristown, New Jersey. A lacrosse power attended by the exceptionally privileged sons of Wall Street titans, Delbarton has for decades been feeding its best to the Ivy League universities…and to wannabes like Duke. Delbarton grads figure prominently in this story.

So handsome and worldly are these teen-age Northern gods replanted in the American South that in recent years they have taken control of Duke’s undergraduate social life, at the very time the school has been most anxious to join H-Y-P, Stanford, and others at the apex of the American college pyramid.

As author Bill Cohan (himself a Duke graduate, like this reviewer) reports in these many pages, the University would now stop at nothing to keep pace with its dream of dominating not just its own region, but the United States itself by becoming “world-class” (a mantra lately heard often in Durham) in athletics and academics alike.

Central to this drive was former North Carolina Governor, U.S. Senator, and Duke President Terry Sanford and his insatiable need to, above all else, raise money for the University by any means available (see Daniel Golden, THE PRICE OF ADMISSION: HOW AMERICA’S RULING CLASS BUYS ITS WAY INTO ELITE COLLEGES—AND WHO GETS LEFT OUTSIDE THE GATES [2006]).

When the drive reacted almost chemically with the rise of Coach Mike Krzyzewski’s soon-to-be unstoppable basketball program, the recruitment of celebrated liberal faculty through expensive raids elsewhere (who would prove to be no friends of spoiled rich jocks from Eastern preppydom), and a shocking turn south in on-campus moral practices, the formula for almost certain disaster was in place.

Within twenty years Duke would evolve into very much the school that non-Dookies love to hate—rich, spoiled, ambitious, arrogant, totally unable to view itself objectively. By 2006, it was the lax boys-- surprisingly, not the more famous basketballers—who were fully in control of the campus where sex was now everywhere and promiscuous “hooking-up” went on non-stop. Seemingly everyone partied every night from Thursday through Sunday, and adults did nothing to temper this ongoing bacchanalia. Although some faculty were appalled by the blatant anti-intellectual atmosphere controlled by the frats and the jocks—and a few even said so—the hapless administration seemed powerless to do anything.

Into the breach, in June 2004, stepped a new President, Richard H. Brodhead, a Yalie darling who had been recruited by many schools, and it was Duke that got him. Brodhead appeared to embody precisely the glamour, pedigree, savoir faire, and smarts that the on-the-make University so desperately hoped to emulate. But it was not to be.

The unprepared Brodhead was immediately tossed into the deep end of the pool by an unprecedented $40 million offer to Coach K to abandon little Durham and repatriate in La-La Land as new head coach of the Los Angeles Lakers (the driving force behind the extraordinary offer was apparently Lakers star Kobe Bryant, a long-time Krzyzewski-admirer who often said that if he had played college ball it would have been at Duke). Cohan describes this as virtually a ploy on Coach K’s part to diminish the dazzling new President and put him in his place by showing who really was—and would remain—in charge at Duke.

Brodhead, terrified that the celebrated coach might depart just as he was coming in, played his obsequious role flawlessly, kneeling at least as deeply as any other K-worshipper in publicly urging Mike to stay at home. In retrospect, he never recovered from this first lesson in humility. Many at Duke—including outspoken ESPN basketball analyst Jay Bilas, a star on Krzyzewski’s first of eleven Final Four teams—saw him as entirely unworthy from this early moment on.

Two years later, the lax boys threw a party at their-Duke-owned house just off the school’s Georgian East Campus. The ostensible excuse for the party was that it was spring break and the team was obliged to remain on campus to prepare for the upcoming NCAA national lacrosse championship, which many saw them as favored to win.

Ranked second in the nation, the boys were living up to their reputations in every way—winning on the pitch, making decent grades in questionable majors, bedding the best women, drinking all the while…basically just being cool and doing whatever they chose to do. This particular party was fueled further by $10 thousand in cash for “lunch money” by their coach Mike Pressler, national lax “Coach of the Year” the previous season.

To add life to their party, the boys hired two “dancers” for $400 each to provide entertainment. Crystal Mangum, a single mother, and Kim Roberts accepted the invitation and the mayhem was on. By the end of the evening, Mangum had claimed that she had been brutally raped by from two to twenty of the Duke players (all of them white), one of whom she said employed a broomstick as a tool.

Mangum’s claim instantly went viral, soon to the entire nation. At first everybody within hearing seemed quick to assume the guilt of the boys—everyone from Brodhead and his unctuous Board of Trustees, the press from “The New York Times” to the “Durham Herald-Sun,” news vultures from Nancy Grace to Selena Roberts, half the Duke faculty, and, above all, Mike Nifong, a little-known lawyer who wanted to be Durham’s new District Attorney.

Once the story was spread, it wouldn’t go away, even after negative DNA tests were returned and countless contradictory tales had surfaced about what may or may not actually have happened that evening.

Despite mounting evidence that there had been no rapes, that Mangum was either a liar or delusional, that Nifong was corrupt and irresponsible, and that the three boys whom he indicted for rape were “innocent,” as proclaimed by the Court in a judgment rarely rendered,* few people seemed to care, at least not for months.

*Courts typically find defendants “guilty” or “not guilty,” hardly ever “innocent,” a personal characteristic beyond proof.

In the end, only Nifong went to jail (for one night), the boys were released, Duke bought them off for a reputed $100 million (thus the title of Cohan’s book), Nifong was disbarred, Brodhead’s ineptitude was rewarded with a new five-year contract courtesy of the Trustees who had hired him (after all, the University was in the midst of a mega-billion dollar capital campaign!), and Duke appeared to emerge from it all largely unshaken. Both applications and donations to the University spiraled sharply up the very next year.

Appalled by all of this, an angry Cohan (author of three best-selling books on business) here spins out an undisciplined mess of a tale, replete with repetitiousness, redundancy, and sloppiness. Still, the story remains so sordid that his abominable book cannot be put down.

You read on, despite yourself. In the end, everyone having anything to do with the tale comes out a loser—most of all Duke University itself (whatever the continuous rise in its numbers). There is little left to admire about it, not even its sainted basketball coach who was largely silent throughout the ordeal.

But so what?! Despite the venality of every player—including the spoiled preppies, viewed still by many as anything but “innocent,” especially after their shockingly greedy law suits—the story ends up with no real lesson, no true “meaning” to be learned.

An already rich Duke got even richer, more spoiled kids than ever clamored to be admitted, and “US News and World Report” continued to rank the disgraced University and its obviously weak leadership, faculty included, as the seventh best “research university” in the United States (tied with MIT and Penn). In the five years since the “rape/lax scandal,” the firing of the coach, and the temporary shut-down of the lacrosse program, it was business as usual in Durham, with Duke winning three national lax championships in that brief period of time.

✺✺✺

By admin

Readers Comments (1)

Sorry, comments are closed on this post.

“By 2006, it was the lax boys– surprisingly, not the more famous basketballers—who were fully in control of the campus where sex was now everywhere and promiscuous “hooking-up” went on non-stop. Seemingly everyone partied every night from Thursday through Sunday, and adults did nothing to temper this ongoing bacchanalia.”

This is ridiculous. An article in Duke magazine in 2005 described the lacrosse team as virtually ‘unknown’ and anonymous on campus; and stated that this relative anonymity was an aid to their academic work.

But the “narrative” for the ‘bad boys gone wild” theme doesn’t read as well that way, does it?

Cohan’s book repeats a great many distortions of the contemporary media-giving them renewed credence. This is, to say the least, unfortunate, especially for someone attempting to write an historical account.