PRESS THE PRESS » WIKILEAKS

An Unethical Record – Stratfor & the New York Times

August 24, 2012 · 1 Comments

By Chris Spannos:

Three months after WikiLeaks began publishing The Global Intelligence Files — more than 5 million e-mails from the private intelligence gathering company Stratfor — New York Times London Bureau journalist Ravi Somaiya told his readers “WikiLeaks has not released any significant material for more than a year.” (“Deportation Decision Awaits WikiLeaks Founder,” May 29, 2012, NYT) Yet on the day The Global Intelligence Files were released (February 27, 2012) WikiLeaks conveyed that Stratfor has paid diplomatic sources; advocated for the psychological and material mistreatment of at least one informant; sought to utilize early access to intelligence for a strategic investment fund by creating a vehicle (StratCap) that would “trade in a range of geopolitical instruments, particularly government bonds”; monitored activists, including for its client Dow Chemical; and engaged in secret deals with media organizations. Somaiya’s dismissive superciliousness of The Global Intelligence Files is indicative of the Times’ treatment of WikiLeaks.

Through NYT eXaminer’s (NYTX) participation in an investigative partnership organized by WikiLeaks we have had access to The Global Intelligence Files and found material that the Times should find significant. The material shows that Times journalists rely on Stratfor despite the company’s interests in advancing U.S. corporate and government dominance at home and abroad, enhancing government secrecy and eroding civil liberties. In addition, Stratfor maintains a perverse relationship with its informants, which is incongruent with the Times’ own standards for the treatment of sources. The Global Intelligence Files also highlight examples of Stratfor employees consciously manipulating journalists at the Times — some of whom seem all too willing to be led by the inauspicious Texas-headquartered “global intelligence” company.

Stratfor claims to be “objective” and “non-partisan” but Times Editors are not oblivious to the company’s motivations or the fact that they gather intelligence in unethical ways. In 2003 Times reporter Matt Bai met with Stratfor CEO George Friedman on the eve of the U.S. invasion of Iraq for an auspiciously timed profile of the company. The profile highlighted Stratfor’s belligerent attitude towards human rights and international law. Bai reported that George Friedman could “live with” a “slaughter” of the Kurds “if that would enable the Americans to get to Baghdad quicker.” (“The Way We Live Now,” Matt Bai, NYT, April 20, 2003). Despite such crass overtures, the Times provide Op-Ed space for George Freidman and lends credence to Stratfor analysts. Further, George Friedman argued in his recent essay “The Geopolitics of the United States: The Inevitable Empire,” that the “final imperative” for the U.S. as a dominant power is to “keep Eurasia divided among as many different (preferably mutually hostile) powers as possible.” Eurasia comprises the continental landmass of Europe and Asia and contains more than 70% of the world’s population.

Three years ago — preceding Obama’s mission in Pakistan which led to the extrajudicial assassination of Osama Bin Laden, the president’s secret orders to send waves of cyberattacks against Iranian nuclear facilities and his “Secret Kill List” to assassinate human targets by drone warfare — the Times published George Friedman’s Op-Ed “Afghan Supplies, Russian Demands” (February 2009, NYT), insisting that the Obama administration should “rely less on troops, and more on covert operations like the C.I.A.” in Afghanistan. Friedman’s preference for covert operations is interesting as these operations often escape public scrutiny and accountability, erode civil liberties and make a folly of international human rights and humanitarian law. Stratfor’s cavalier contempt for transparency reveals un-democratic tendencies antithetical to the ideal of an informed civic with the capacity to participate freely and fully in society — enabling the free and equal practice of self-determination. Though, is perhaps unsurprising given Stratfor’s involvement in the TrapWire “counterterrorist” surveillance system used to monitor activists (Doc-ID: 5355966). (“TrapWire and Stratfor are business partners,” August 15, 2012, Darker Net)

Despite Stratfor’s (at best) ambivalence toward — and at worst support for — war crimes, advocacy for covert war, participation in the corrosion of privacy rights and cheerleading for Empire — often in the Times own pages — the e-mails obtained by WikiLeaks reveal that the Times Senior terrorism and national security writer Eric Schmitt (Doc-ID: 577559), London Bureau chief John F. Burns (Doc-ID: 501124) and others (Doc-ID: 12750) hold the information provided by Stratfor in high regard and value easy access to it. Many other Times journalists also hold accounts and their News Directors have sought Foreign Desk and bureau-wide access (Doc-ID: 620711). In 2009, Stratfor said they had 34 readers “with an @nytimes.com email address.” (Doc ID: 219254). Two Times journalists, Jane Perlez and Carlotta Gall, became close to the company following a meeting in Pakistan with Stratfor’s South Asia director Kamran Bokhari. The Times journalists sought and gained access to Stratfor intelligence and reciprocated by publishing Bokhari’s views six weeks later in “Rebuffing U.S., Pakistan Balks at Crackdown.” (October 14, 2009, NYT)

Intelligence vs. Journalism & the Unethical Treatment of Sources

|

Stratfor & the |

| Stratfor is a small private contractor in an otherwise sprawling private and government U.S. counterterrorism network that has expanded substantially since September 11, 2001. According to the Washington Post’s 2010 investigation “Top Secret America,” this network is connected by 1,271 government organizations and 1,931 private companies. These institutions work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in about 10,000 locations across the United States. The investigation also reveals that "An estimated 854,000 people, nearly 1.5 times as many people as live in Washington, D.C., hold top-secret security clearances." |

Stratfor, founded in 1996, describes itself as specializing in “geopolitical analysis” for individual and corporate clients (in practice their clients include government agencies too). The company is privately owned and under the top-down leadership of founder and CEO George Friedman — who is the company’s Chief Intelligence Officer and financial overseer. (Doc-ID: 898587) George Friedman’s wife, Meredith Friedman, is the Chief International Officer and Vice-President of Communications. Fred Burton, formerly a special agent with the U.S. Diplomatic Security Service, is Stratfor's Vice-President for Counter-Terrorism and Corporate Security. Both report directly to George Friedman. Next in-line, the “Watch Officers,” comb over intelligence. Stratfor “Analysts” (also called “Handlers”) discuss and scrutinize intelligence, and find and build “relations with individuals in order to exploit information.” Stratfor informants form the essential base of the hierarchy. (“Stratfor: Inside the World of a Private CIA,” February 27, 2012, Al Akhbar) Stratfor offers three types of intelligence: “Situational Awareness,” which they describe as “knowing what matters”; “Analyses” telling their members “what events in the world actually mean”; and “Forecasting” which, they claim, are “analytically rigorous predictions of what will happen.” In deciding what matters, what events mean and what will happen, Stratfor is driven by the interests of its paying clients, including Dell computers, Coca-Cola, Raytheon and many others.

In an era of reducing funds for investigative journalism, Times’ reporters are increasingly under pressure to provide breaking news and apt analysis under tight deadlines. Journalists often rely on — and repeat without investigation — State Department and Whitehouse statements and press releases. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that Times journalists also rely on intelligence organizations such as Stratfor to provide quick and easy access to information and analysis that can form the basis of new articles by journalists. However, blind reliance by Times journalists on organizations beholden to corporate interests and with little regard for international law or ethics on the treatment of informants or sources cannot go unquestioned.

Stratfor CEO George Friedman publicly contends that Stratfor’s intelligence analysts (in contrast to media outlets) provide value-added, forward looking, information on why and what next, “That’s really where Stratfor differs from a journalistic organization. A journalistic organization is essentially backward looking.” (About Stratfor: Intelligence vs. Journalism) Privately, however, George Friedman seems to accept a less rhetorically sophisticated distinction, “We are not at all like the [NYT] because their reporters always identify themselves as such. We may or may not as it suits us. This is the fundamental difference between journalism and intelligence. The source may never know he was a source, which is the definition of clandestine.” (Doc-ID: 1196088). In his 2003 profile on Stratfor for the Times, Matt Bai described a perverse customer relationship where, “Some of Stratfor's 150,000 Web subscribers [reportedly 292,000 as of July 2011 (Doc-ID: 84934)] -- who include devotees in the military, foreign governments and Fortune 500 companies -- have become informants as well.” (“The Way We Live Now,” NYT, April 20, 2003) The “Stratfor Glossary of Useful, Baffling and Strange Intelligence Terms” explains that their own definition of a source is “anyone who has ever talked to an intelligence agent” and that a source can mean “anything from having once been told to move on by the guard at the gate to screwing the President’s wife.” (See glossary)

The New York Times’ “Ethical Journalism: A Handbook of Values and Practices for the News and Editorial Departments” (NYT, 2004) states that “Reporters, editors, photographers and all members of the news staff of The New York Times share a common and essential interest in protecting the integrity of the newspaper.” The Times’ handbook tells its staff that they “may not threaten to damage uncooperative sources.” (NYT, 2004) But Stratfor assert that “All sources need to be squeezed.” It is further elucidated that one way to squeeze a source is by “Showing 5x7 glossies of certain unfortunate incidents to his wife…” Stratfor describes a “coerced source” as someone who is an informant “because you have him by the balls.” But a source can also be a “contractor” under terms and conditions that “spells out what he gets, when he gets it, what he must deliver, and where he will find various parts of his body if he jerks you around.”(See glossary) The Times tells its staff that they “may not pay for interviews or unpublished documents.” (NYT, 2004) Yet Stratfor’s glossary proposes that sources “can work for $50 a month or $5 million a year.” (See glossary)

The Times insist that its staff “treats news sources just as fairly and openly as it treats readers,” and that they “do not inquire pointlessly into someone’s personal life.” (NYT, 2004) But Stratfor CEO George Friedman ordered Director of Analysis Reva Bhalla to violate a Venezuelan source in exactly this way, “If this is a source you suspect may have value, you have to take control [of] him. Control means financial, sexual or psychological control to the point where he would reveal his sourcing and be tasked.” (Doc-ID: 201031)

The Times claim that “Our greatest strength is the authority and reputation of The Times,” and that, “We must do nothing that would undermine or dilute it and everything possible to enhance it.” Yet, the Times have a long and unethical record of relying on Stratfor.

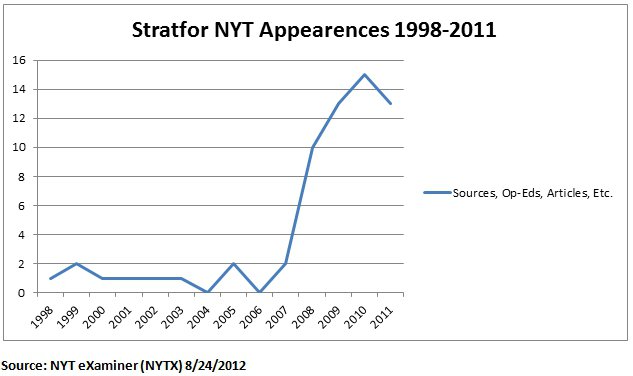

Before 2008 the Times’ reliance on Stratfor as a source for information and analysis was minimal. Between 1998 and the end of 2004, the Times had published only six articles referencing Stratfor. Stratfor CEO George Friedman wrote the very first piece, “Russian Economic Failure Invites a New Stalinism,” an Op-Ed which the Times published on September 11, 1998. Between 1999 and 2002 Times’ journalists sourced various Stratfor reports and one unnamed analyst from the firm. In 2003 the Times published Matt Bai’s profile of Stratfor, “The Way We Live Now.” (April 20, 2003, NYT)

The Times’ reliance on Strafor intelligence spiked in 2008 — a trend that, according to NYTX tracking, continues into this year. Between George Friedman’s first 1998 Op-Ed and May 7, 2012 the Times sourced Stratfor in their content on some sixty six occasions. Fifty six of those have occurred since 2008, averaging more than once per month, every month over a four year and five month period.

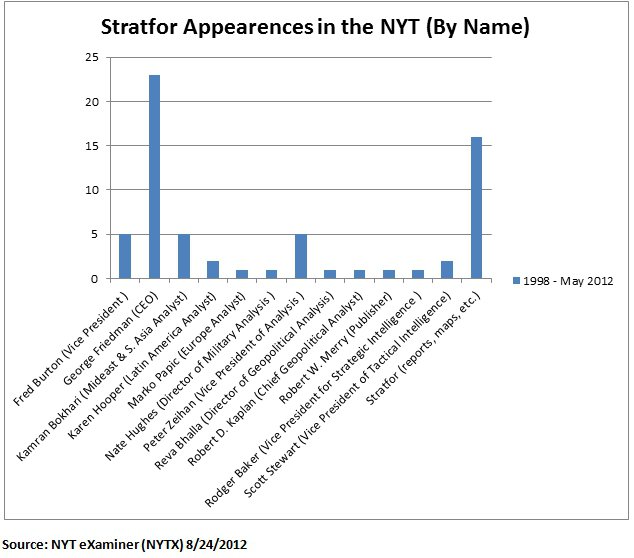

Between September 1998 and May 2012, the Times referenced Stratfor reports, maps, images, and analysis roughly sixteen times; quoted, referenced or paraphrased the company’s Vice President of Analysis Peter Zeihan five times; Mideast & South Asia Analyst Kamran Bokhari five times; Vice President Fred Burton five times; and CEO George Friedman twenty-five times. Many other Stratfor analysts were also sourced. More worryingly, Times journalists have also published Stratfor intelligence and analysis as their own. As this occurs without citing Stratfor, we cannot ascertain how often this occurs. (Doc-ID's: 1765641, 1822533, 1780740, 1691055, 5101192, 2232067, 1317065, 1338652)

The “Paper of Record” as Public Relations Platform

| Business as Usual: The NY Times Co. & Stratfor |

| Some Stratfor corporate clients share the same board members as the New York Times Company. Raul E. Cesan, a Times Co. Director since 1999 is also a current Director of Gartner, Inc., an IT consulting company which has been paying for yearly Stratfor services since at least 2006 and which renewed its 2011-2012 Service Agreement last year. (Doc-ID’s: 514663, 468513, 18233, 555824, 1417567 and 2824903) Times Co. board member Robert E. Denham is also a board member of the Chevron Corporation — which McClatchy’s reported was Stratfor’s largest client in 2011, paying $81,700.00 for services. (“WikiLeaks: Stratfor emails reveal problems with Web security,” February 29, 2012). NYT eXaminer’s investigation adds to McClatchy’s report by revealing that since 2009 Chevron Corporation’s Latin American Business Unit has spent approximately $160,000.00 on Stratfor services designed specifically to monitor Venezuela. (Doc-ID’s: 5463685 and 2816597). Stratfor’s 2011 invoice for Chevron included these billing details: “IMPORTANT--The client has asked us to remove any reference to ‘Venezuela’ or ‘intelligence’ from the invoice.” (Doc-ID: 2795370) |

Under U.S. law Stratfor is obliged to act in the best interests of its shareholders and thus increase profits. Not unusually, one marketing strategy is to spread its company’s “Core Brand Identity.” However, this involves “Low Cost Advertising,” which means establishing Stratfor analysts as “‘Credible Experts’” through “media placement.” So Stratfor tracks all its media appearances. One implication for journalists that rely on Stratfor intelligence or analysts therefore is that they are carrying out a public relations strategy for Stratfor. (Doc-ID: 1344762) What does Stratfor view as its core brand identity? A possible answer would be the provision of strategic analysis and information that is in the interest of its existing and potential client-base. This would explain their strategy to target “media outlets according to audience profile.” (Doc-ID: 1304054) By placing information in strategically important places, Stratfor not only increases its chances of obtaining new clients, it also exploits information in the interests of its existing clients, impacting public opinion on key policy issues for the benefit of its clients. It is by doing this that the company increases the likelihood of obtaining new clients.

Stratfor is aware of the considerable credibility that presence in the Times lends and so the unique public relations role that the paper can play for them. When the Times interviewed Stratfor analyst Karen Hooper in 2009 the company’s Public Relations Manager (Brian Genchur) congratulated Hooper on the achievement, “Top interview in the story! Great job, Karen.” But CEO George Friedman honed in on what was important, “Great for our QSM branding to be in NYT.” (Doc-ID: 13155). E-mailing about another article sourcing Stratfor, Meredith Friedman claimed “Pretty good for a NYT reporter:) And wonderful for Stratfor. This will help brand us more than many other places we are quoted.” (Doc-ID: 3531311) And when Times’ reporters Damien Cave and Ravi Somaiya interviewed Fred Burton for their November 4, 2011 article “Facts Blur as Online Feud Ends in a Draw,” Stratfor continued to track its publicity, “3rd mention in NY Times in less than 7 days.” (Doc-ID: 1316654)

The Times also lends its credibility to the company by providing prominent placement for Stratfor intelligence and by using it in feature stories surrounded by other sources with higher credentials such as presidents and diplomats. “George [Friedman] was quoted in a New York Times article today on Obama's foreign policy options given the results of the recent election. His quote is very prominent (3rd paragraph, first expert quoted) and they included a link to the homepage. This is a great mention for STRATFOR - nice work, George,” wrote Public Relations Manager Kyle Rhodes. (Doc-ID: 1348631) (“For Obama, Foreign Policy May Offer Avenues for Success,” November 4, 2010, NYT) This Times’ article perfectly highlights the way in which journalists at the paper will give credence to Freidman’s recommendations for how the U.S. can most effectively wield its geopolitical and economic power. In this particular case, Friedman argues that president Obama “could threaten to close the American marketplace to China if it did not revalue its currency.” In this piece, alternative suggestions for full employment programs and higher wages to lessen extreme and unsustainable disparity in wealth are noticeably absent. Also absent are statements outlining what the impact of closing the American marketplace to China would be for consumers in the U.S. and Chinese workers who currently serve U.S. and western consumer interests, often in inhumane conditions. Suggestions to initiate policies that would reduce unprecedented inequality in the U.S. are often met with disdain by large corporations that include George Friedman’s paying clients.

That journalists repeat Stratfor’s analysis, intelligence and information in their articles, often without questioning, conveys a bias towards publishing news fit to print for a specific group in society — business owners and entrepreneurs, service providers that act in the interests of business owners and entrepreneurs and government officials who are consistently — and successfully — lobbied by such folk. The revolving door between government and business suggests that those lobbying often become the lobbied and vice versa. Indeed, as we have seen, the Times consistently gives Op-Ed space to Stratfor CEO George Friedman, sources Stratfor in articles and occasionally seems to overtly market Stratfor, such as the Times’ June 2002 piece which described Stratfor’s various intelligence company rates and services. (“Dangerous locations: Security risks often underrated,” June 22, 2002, NYT)

Beyond their strategy of “Low Cost Advertising” product placement, NYT eXaminer’s investigation found that Stratfor has spent tens of thousands of dollars exploiting the Times’ prestige to inflate their own reputation as “Credible Experts.” They have bought their way into the Times’ bestseller booklist on a number of occasions. Promoting Vice President of Intelligence Fred Burton’s 2008 memoir Ghost, Aaric Eisenstein, Stratfor’s VP for publishing, wrote “I've told Random House that we'll order through B&N [Barnes & Nobel] to push Fred's book onto the NYT Bestseller List…it costs us about $4K to buy our way onto the list.” (Doc-ID: 3635756) Similarly, Stratfor sold several thousand copies of George Friedman’s book The Next 100 years before having it in stock to get it on the list (Doc-ID: 1271821). And for George Friedman’s following book The Next Decade, Stratfor purchased 2,339 copies for $52,012.32. Their purchase put George Friedman’s book on the Times’ “bestseller” list early the following month. (Doc-ID's: 267008, 1422548 and 254534).

Part of Stratfor’s plan for this last book was to offer The Next Decade as a free gift to potential Strafor subscribers. But at least one person rejected the offer writing “Oh, man! We have had Thomas Friedman, the New York Times world-is-flat columnist, and Milton Friedman, the free-market academic economist, who till his last day, preached how wonderful free-market world is. And now, another Friedman -- that's you -- have come with a new book…With all due respect, I think we have had enough Friedman[’]s and their papal talkies.” (Doc-ID: 473739)

Two-Faced Social Competitors

While opportunistically using the Times as a platform for self-promotion Stratfor simultaneously views the paper as a social competitor. On the one hand Stratfor analysts use the Times to measure the efficacy of their own work. On the other hand they revel in the possibility of garnering potentially damning information about the paper and often express animosity towards it. Stratfor’s China Director Jennifer Richmond explained that their media partnerships — which exclude the Times — are how they “hope to get an edge up on publications such as NYT.” (Doc-ID: 1748912) And outlining his understanding of the Times’ dependency on Stratfor, Director of Multimedia Brian Genchur wrote, “The reason media come to us for information and analysis is because we are, by definition, not open source. If we named all of our sources the same way the NYT does, then they would likely go to the 'primary source' of the information (where we collected it) rather than us. The NYT wouldn't analyze it as well, but that's another point.” (Doc-ID: 1196088)

Stratfor recognizes that in order to effectively propagate advice in its clients’ interests the company must be perceived as providing credible expertise, which means that Stratfor analysts have to appear in the “paper of record.” The company also recognizes that its exploitation of information reaches an important and influential audience in the Times readership. The New York Times’ audience, however, is also the same readership that Stratfor would like to have paying subscription on its site, creating the simultaneously mutually dependent and competitive relationship.

Despite trying to get an “edge” up on the Times Stratfor analysts regularly discuss the paper’s articles for the insight they provide (Doc-ID: 1125785) and to corroborate their own work. Sometimes Stratfor will confer with one of their own covert sources to get a second opinion about information that the Times published. (Doc-ID: 119490) However, despite Stratfor’s use of the Times as a tool to assess their own work, Stratfor analysts often dismiss and belittle the paper. “As with most NYTimes articles it doesn't say anything new and most cogent things it does say we said 6 months ago,” wrote Stratfor analyst Marko Papic. (Doc-ID’s: 1672247, 1796025 and 1732382) VP of intelligence Fred Burton has said in relation to another article, “Nothing new here [.] Because the NYT says it, it becomes news.” (Doc-ID: 386775) Nonetheless, the same Stratfor analysts that criticize the paper jump at the first opportunity to appear in its pages. On January 4, 2011 Liz Alderman, Chief Business Correspondent for the International Herald Tribune, Global Edition of the New York Times, wrote to Stratfor stating, “I saw Marko Papic's video analysis on the China vice premier's European visit this week, and I would like to interview him by phone for a story I'm working on about China's intentions here….” Stratfor’s Kyle Rhodes asks Papic, “got time for this today?” Papic, does not hesitate, “Uh... hell yeah...” (Doc-ID: 1694453) Alderman’s interview with Papic resulted in her January 6, 2011 article “Beijing, Tendering Support to Europe, Helps Itself.”

At the same time, Stratfor’s competition with the New York Times means that they relish digging up dirty information that could ruin the paper’s reputation. When news broke in 2009 that Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim was going to loan the Times $250 million dollars via cash infusion, Fred Burton wrote “It would be interesting to see what [Drug] cartel [Slim] is beholding too. Wonder how much drug money is being laundered into this transaction?” Aaric Eisenstein replied, “Find out. Would make an AWESOME campaign. Just say no to the NYT!” (Doc-ID: 3447461). Stratfor client Dell computers made an unrelated inquiry just months before the Times paid off their loan to Slim in August 2011. (Doc-ID: 411681) And Burton asked his contact at the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) responsible for Mexico (MX), “Billy, Is the MX billionaire Carlos Slim linked to the narcos?” Without offering any evidence, Billy replied “The MX telecommunication billionaire is......” (Doc-ID: 1208803)

When the Tail Wags the Columnist

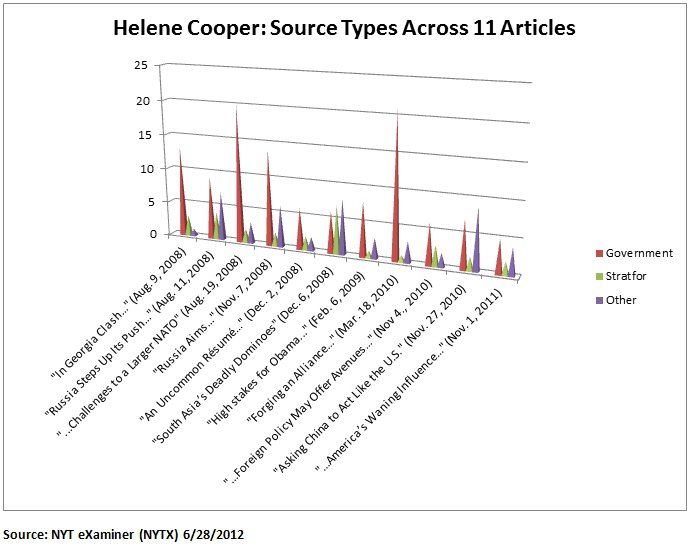

Stratfor works hard to build relationships with Times journalists so that writers at the paper may be more inclined to rely on Stratfor analysts. But on other occasions, Stratfor employees have gone further to consciously manipulate Times reporters, such as their explicit manipulation of Times White House correspondent, Helene Cooper. In 2008 the number of times the paper referenced Stratfor increased substantially. In the last half of that year, Cooper relied on CEO George Friedman six times (three times in August alone and three times between November and December). Beginning in 2009 Cooper’s own reliance on Stratfor diminished, but her declining use coincided with an overall increase by her co-reporters. This overall increase resulted in the Times sourcing Stratfor fifty-six times since the beginning of 2008, averaging more than once per month, every month, over a four year and five month period.

NYT eXaminer’s analysis shows that Cooper relied heavily on CEO George Friedman citing him in ten of eleven articles. On the single occasion that Cooper sourced a Stratfor analyst other than George Friedman it was because he was not available and another analyst was recommended, “Helene - we're actually in Kiev now but heading to Warsaw tomorrow. You really should talk to Rodger Baker…” (Doc-ID: 289986). Cooper agreed and interviewed Baker for her article that the Times published three days later. (“Asking China to Act Like the U.S.,” November 27, 2010, NYT) While Cooper also sourced many diplomats and government officials, they gave restrained and sometimes anonymous quotes. Reliance on Friedman allowed Cooper to publish unrestrained “forecasts” and speculation. That Cooper did not rely on any non-governmental source with as much fervor conveys her favoritism towards George Friedman and Stratfor.

Furthermore Cooper’s articles gave George Friedman a pedestal from which to articulate how geopolitical developments would affect U.S. power. On the December 2008 Mumbai massacre Friedman said this effected Obama’s “intricate construction for what might happen in South Asia with the right American push.” (“South Asia’s Deadly Dominoes,” December 6, 2008, NYT) When Kyrgyzstan legitimately closed a U.S. base, it was interpreted “as a shot across the [American] bow.” Instead of recognizing that Kyrgyzstan might not have wanted the U.S. base on its soil, blame for the closure was put on Russia. Cooper quoted George Friedman’s opinions on how the U.S. would have to “make a strategic decision on what is more important, their Russia policy or their Afghan policy." Not once did Cooper quote Russian, Kyrgyzstani or U.S. peace activists. (“High stakes for Obama at weekend security conference,” February 6, 2009, NYT) Similarly in her articles sourcing Stratfor she failed to interview experts that could advocate for the primacy of human rights and international law in the arena of international relations.

| Helene Cooper's 11 Articles |

|

Stratfor saw the potential to make Cooper a conduit from the very first article she sourced them in, “In Georgia Clash, a Lesson on U.S. Need for Russia,” (August 10, 2008, NYT). Meredith Friedman wrote, “Think we've developed a good relationship with her and will keep her updated on what's happening. Will also teach her what's important to look for in this conflict!!” Clearly it is inappropriate for a company whose CEO has shown disregard for accountability, transparency and human rights to be teaching any journalist what is “important” in a conflict.

It gets worse. Referring to Cooper’s first article sourcing Stratfor another analyst, Aaric Eisenstein, reacted, “This is the article I circulated to allstratfor [e-mail list]. It reads like George wrote the whole thing for her.” George Friedman replied, “I sort of did.” (Doc-ID: 3513561) That Cooper would plagiarize Stratfor’s work — or allow George Friedman to ghost write a Times article for her — is rather astounding and clearly a breach of Times conduct, “Staff members who plagiarize or who knowingly or recklessly provide false information for publication betray our fundamental pact with our readers…” That Stratfor would allow Cooper to — willingly — co-opt their analysis is interesting and suggests that — rather than simply being in the business of publishing objective and impartial strategic intelligence, Stratfor is in the business of seeking to influence public perception on policy issues in favor of its clients’ interests and recognizes the opportunity to do this through the Times.

Although Cooper was willing, and even at times eager, to publish Stratfor intelligence in her articles, NYT eXaminer did not find any evidence that Cooper knew that Stratfor was teaching “her what's important to look for” or that she willingly agreed to let George Friedman write at least one article for her. Yet, Cooper displayed her willingness to work with Stratfor not long after in her article, “South Asia’s Deadly Dominoes” (December 6, 2008). In this article Cooper published Stratfor intelligence again with their analysts reacting, “Great placement in the Week in Review section of tomorrow's paper… the reporter laid out George's 5 point [scenario] he gave in an interview. This is great exposure for Stratfor.” (Doc-ID: 1803489) She has published nine other articles sourcing Stratfor since, eleven in total.

From 2008, Helene Cooper seemed to recommend Stratfor to other Times journalists and Editors. Cooper perhaps needs to be reminded of the Times “Ethical Journalism” handbook which clearly states that:

Relationships with sources require the utmost in sound judgment and self discipline to prevent the fact or appearance of partiality. Cultivating sources is an essential skill, often practiced most effectively in informal settings outside of normal business hours. Yet staff members, especially those assigned to beats, must be sensitive that personal relationships with news sources can erode into favoritism, in fact or appearance. And conversely staff members must be aware that sources are eager to win our good will for reasons of their own. (NYT, 2004)

In 2009 Meredith Friedman wrote that she was going to send Cooper and other reporters their press release “because I've had a long and strong personal relationship with them.” (Doc-ID: 271755) In 2010 Meredith wrote another Times White House correspondent Mark Landler, “Helene Cooper suggested you might be interested in attending STRATFOR's China event…” (Doc-ID: 289379) That same year Cooper provided contact information for a Times Editor so that George Friedman could submit an Op-Ed. (Doc-ID: 289583) And the very same day that Cooper sent the Editor’s contact information George Friedman appeared in two separate Times’ articles. Cooper authored one of these articles and sourced George Friedman as “of Stratfor.” (For Obama, Foreign Policy May Offer Avenues for Success,” November 4, 2010, NYT) The second article that day, by Alan Cowell, failed to source George Friedman as having any connection to Stratfor, much less being its CEO. Cowell cited him instead as “an American foreign affairs specialist.” (Abroad, Fear That Midterm Result May Turn U.S. Inward,” November 4, 2010, NYT) While Cooper’s article focuses on Obama’s foreign policy and Cowell’s on domestic elections, both journalists allow George Friedman to pontificate on Obama in November 2010 as an American leader weakened at home and needing to compensate with strong foreign policy abroad to secure America’s role in the world, the implication being that U.S. interests take precedence over impoverished and vulnerable populations abroad.

Conclusion

The perverse relationship between Stratfor and the New York Times — documented in this report and spanning from September 1998 to May 2012 — is one example of the problems with dominant media’s reliance on powerful corporations and governments and vice versa. Rather than encouraging its journalists to act as diligent checks on power, New York Times journalists have appreciated having access to privately owned, clandestinely gathered information and analysis. Stratfor has benefited by having wide ranging access to the Times pages, including direct access to journalists — and in some cases control over what they publish — and by even exploiting the paper’s “bestseller” book list. But Stratfor is dependent on — at times grossly unethical and illegal — covert intelligence gathering. This presents problems for all media institutions aspiring toward ethical practices and conduct that rely on such companies.

On April 14, 2010, just days after WikiLeaks released its “Collateral Murder” video, Times columnist Noam Cohen wrote Stratfor’s Vice-President for Counter-Terrorism and Corporate Security, Fred Burton, to request an interview focusing on WikiLeaks, “the amorphous, Web-based organization that recently published a video taken from an Apache helicopter during an attack that killed 12 civilians, including two reporters [from] Reuters.” (Doc-ID: 397697) Rather than congratulating WikiLeaks on the publication of a video that informed the U.S. public of its government’s action abroad and shed light on the actions of the occupying forces, Burton argued in Cohen’s article, “What Would Daniel Ellsberg Do With the Pentagon Papers Today?,” (April 18, 2010, NYT) that WikiLeaks’ video ultimately “hurts the U.S. intelligence operation’ because it hinders efforts to improve communication among agencies.” Burton’s concern about hurting government intelligence operations can be expected as its client base includes the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and other government agencies, and since it is in the very business of private and covert intelligence gathering. However, it is more surprising that Burton should find an ally to advance his argument in the likes of former Executive Editor of the Times, Bill Keller. Earlier in 2012 Keller, just days before WikiLeaks released their Global Intelligence Files, wrote that “The most palpable legacy of the WikiLeaks campaign for transparency is that the U.S. government is more secretive than ever,” (“WikiLeaks, a Postscript,” February 19, 2012, NYT) Such claims negate the important function that WikiLeaks plays in attempting to bring some check on the exercise of power by informing the public and thus fermenting demand for transparency and accountability. They are also rather hysterical claims when they come from an Executive Editor who has sought governmental approval of Cablegate publications at every corner, providing the government with shelter from possible calls for transparency and negating its duty “to give the news impartially, without fear or favor.” (Times’ patriarch Adolph S. Ochs (1896))

In its landmark 1971 ruling in The New York Times Co. v. United States concerning the publication of the “Pentagon Papers” the Supreme Court upheld the press’s constitutional rights and responsibilities claiming that “In the First Amendment, the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to [fulfill] its essential role in our democracy. The press was to serve the governed, not the governors.” Rather than inform the public of information that it deems is in our best interests, the New York Times has instead given “early warning” to “Representatives from the White House, the State Department, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the C.I.A., the Defense Intelligence Agency, the F.B.I. and the Pentagon” and selectively published WikiLeaks’ Cablegate data that was approved by U.S. government agencies. (“Dealing With Assange and the WikiLeaks Secrets,” January 26, 2011, NYT) The long-term consequences of this choice are far reaching — potentially impacting press freedoms and civil liberties around the globe. (“The Fourth Estate Forfeiting Its Own Press Freedoms: WikiLeaks & The New York Times,” February 8, 2012, NYTX)

The New York Times recently reported that an F.B.I hunt for high-level government officials from diverse agencies coincided with the Senate Intelligence Committee’s approval of legislation “designed to curb intelligence officials’ exchanges with reporters.” The F.B.I’s investigation reached into the White House, Pentagon, National Security Agency and the C.I.A., and has cast “a distinct chill over press coverage of national security issues as agencies decline routine interview requests and refuse to provide background briefings.” (“Inquiry Into U.S. Leaks Is Casting Chill Over Coverage,” August 1, 2012, NYT) This very real example of the U.S. government becoming “more secretive than ever” is not, as Keller claims, the fault of WikiLeaks. The Times Editorial board recently suggested to its readers that this crackdown on national security journalism and whistleblowers is “In response to recent news media disclosures about the so-called kill list of terrorist suspects designated for drone strikes and other intelligence matters,” that the Times reported in their paper. But the Times managing Editor Dean Baquet denied that these stories were the product of government leaks and explained that those stories “are so clearly the product of tons and tons of reporting.” (“The New York Times: These were not leaks,” June 7, 2012, Politico)

Whether the information was obtained via investigative journalism which did or did not include obtaining leaked material is irrelevant. More reporting of this nature is necessary to ensure accountability. Indeed, the Times Editorial board argues denying citizens access to information “essential to national debate on critical issues like the extent of government spying powers and the use of torture” could “undermine democracy.” Pursuits for truth do not cause government secrecy. Condoning state control over accessibility to information in the public’s interest and creating an environment in which governments and agencies feel entitled to decide upon what information can be made available to the public perpetuates government secrecy.

The problem seems to be between those who want real transparency to expose corporate and government abuse of power and to enhance citizen participation in the democratic process, and those who want to keep these abuses hidden while expanding covert war and keeping clandestine operations off the public’s radar while undermining constitutional protections and international law.

Chris Spannos is Editor of NYT eXaminer (NYTX). NYTX is a media project which advocates on behalf of new editorial standards in mainstream news media including the appropriate application of international law, human rights, and other norms that promote truth and social justice. Website: www.nytexaminer.com

[Note of disclosure: Julian Assange, Founder and Editor of WikiLeaks, is an NYTX Advisory Council Member.]

By admin

Readers Comments (1)

Sorry, comments are closed on this post.

Recommended links

- Best Non Gamstop Casinos

- Migliori Siti Casino Online

- Lista Casino Non Aams

- Casino En Ligne Fiable

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Paris Sportif Crypto

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- UK Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Non Gamstop Casino

- Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Casino Online Non Aams

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- UK Casino Not On Gamstop

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne Fiable

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino UK

- Non Gamstop Casino UK

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne En Belgique

- Scommesse Italia App

- Sweet Bonanza Avis

- 코인카지노

- 파워볼사이트

- лучшие казино Украины

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino Online Senza Documenti

- Migliori Siti Scommesse Non Aams

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino En Ligne France

- Casino Non Aams

- Lista Casino Non Aams

- Casino En Ligne France Légal

Brilliant analysis: well-researched, clearly presented, devastating in its implications. Cjris Spannos has done it again!